Volume: 13 Issue: 3

Awareness, Attitude and Practice Towards Umbilical Cord Blood Banking among Pregnant Women in Tertiary Care Hospital, Hyderabad

Year: 2025, Page: 183-190, Doi: https://doi.org/10.47799/pimr.1303.25.21

Received: June 2, 2025 Accepted: Nov. 19, 2025 Published: Dec. 31, 2025

Abstract

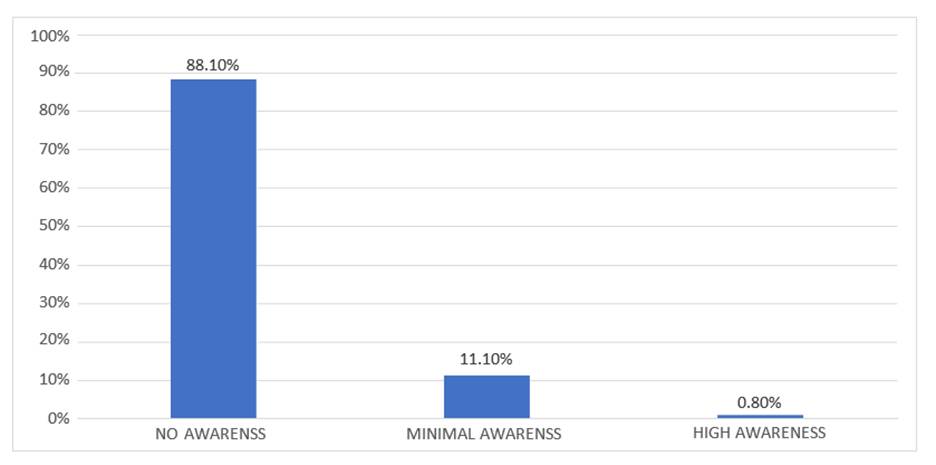

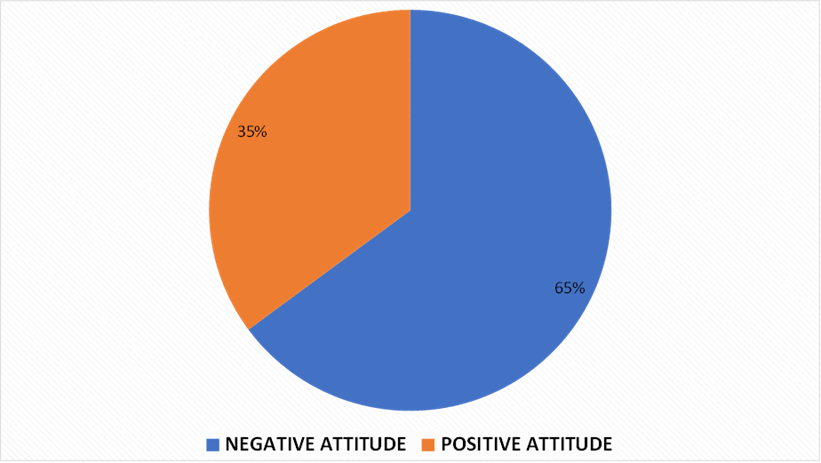

Background: Umbilical cord blood (UCB) is the blood remaining in the placenta and umbilical cord after birth. It contains a high concentration of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells and was once discarded as medical waste. Despite its therapeutic potential, awareness and practice of UCB banking remain limited in India. Understanding current awareness, attitude, and practice is essential to improve utilization. Objectives: 1. To assess the level of awareness, attitude and practice towards UCB banking among pregnant women in a tertiary care hospital, Hyderabad. 2. To assess the association between socio-demographic factors and awareness, attitude, and practice of umbilical cord blood (UCB) banking. Materials and Methods: An analytical cross-sectional study was conducted among 270 pregnant women attending antenatal OPD at a tertiary hospital in Hyderabad, Telangana. The sample size was calculated assuming an awareness level of 28%, 20% allowable error and 5% non-response rate. Simple random sampling was used. A predesigned, structured questionnaire is used for data collection. Data were analysed using SPSS v20; chi-square test was applied with p<0.05 as significant. Results: Among 270 participants, 30 (11.1%) had minimal awareness, 2 (0.8%) had high awareness, and 238 (88.1%) had no awareness. Religion, education, occupation, socio-economic status, and parity were significantly associated with awareness. Regarding attitude, 175(64.8%) of participants were negative and 95(35.2%) positive. Conclusion: UCB banking awareness was poor, though one-third has positive attitude. Strengthening antenatal education is essential for informed decision-making.

Keywords: Cord Blood Stem Cell Transplantation, Pregnancy, Maternal Child Health Services

INTRODUCTION

Umbilical cord blood (UCB) is the blood that remains in the umbilical cord and placenta after childbirth. It is a rich source of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells, capable of differentiating into various blood and immune cell types [1]. Historically considered medical waste, UCB gained recognition after the first successful cord blood transplant in Paris in 1988 [2]. Since then, global network of cord blood banks and transplant centers has been established with a large common inventory, allowing for more than 20,000 transplants worldwide in children and adults with severe hematological diseases [3]. It offers an alternative source to bone marrow and peripheral blood stem cells, particularly when a fully HLA-matched donor is unavailable [4].

UCB banking is categorized into public and private models. Public banks store cord blood units (CBUs) free of charge for unrelated recipients, supporting equitable access to transplants [5, 6]. In contrast, private banks store CBUs exclusively for the donor family, often at significant cost, and are promoted as a form of biological insurance despite the low likelihood of autologous use [7, 8]. In India, private banking dominates due to emotional marketing, limited infrastructure for public banking, and widespread misconceptions regarding cost, ownership, and utility [9-11]. Studies across India have shown that awareness of UCB banking among pregnant women is poor. For instance, only 26.5% knew what UCB stem cell banking meant, and 18.1% were aware of its uses [6]. A recent Telangana-based study reported that only 4.9% of pregnant couples had even heard of UCB banks [11]. These findings underscore the need to assess current awareness, attitude, and practice among expectant mothers regarding UCB banking.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was a hospital-based analytical cross-sectional survey incorporating a brief educational component. It assessed baseline awareness and attitudes regarding umbilical cord blood (UCB) banking among pregnant women, followed by a short educational session prior to attitude reassessment.

Study Area and Population

The study was conducted among pregnant women attending the antenatal outpatient department (OPD) of Gandhi Hospital, Hyderabad, Telangana, India, a tertiary care teaching hospital. Data collection took place between January 2025 and May 2025.

Sample Size Determination

The sample size was estimated for the prevalence of awareness regarding umbilical cord blood (UCB) banking, with P = 28% (based on Anandgaonkar et al. [7]), L = 20% of the prevalence (5.6%), and Z = 1.96 (95% confidence level) using the single-proportion formula N = Z²PQ / L². Allowing for a 5% non-response rate, the required sample size was 261, and the final achieved sample size was 270.

Inclusion criteria

All pregnant women attending the antenatal OPD who provided written informed consent.

Exclusion criteria

Pregnant women who were unwilling to participate in the study.

Sampling Technique

Participants were selected using a systematic random sampling method with a fixed daily quota. The antenatal OPD attendance register (10:00 AM–12:00 noon) served as the daily sampling frame. Each eligible woman was assigned a serial number, and 7–8 participants were chosen daily using a pre-generated random number table over 50 data collection days. This ensured that every eligible woman in the defined period had a known and non-zero probability of selection while maintaining manageable daily recruitment. Non-responders were not substituted on the same day; subsequent day selections proceeded independently to minimize substitution bias. Evening clinics were excluded due to logistic and staff constraints. In total, 296 women were approached, of whom 270 consented to participate, yielding a response rate of 91.2%, indicating high acceptability and feasibility of the study.

Data Collection Tool

Data were collected using a pre-tested, structured questionnaire designed to capture sociodemographic details, awareness, attitude, and practice regarding UCB banking. The questionnaire was pilot tested among 20 pregnant women, who were not included in the main sample, to assess clarity and feasibility. Expert opinion was obtained to establish face and content validity. Internal consistency was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha, yielding values of 0.817 for the awareness scale (7 items) and 0.816 for the attitude scale (4 items), both indicating good reliability. The questionnaire was interviewer-administered in the participant’s local language to ensure comprehension.

Study Procedure

The study was conducted in two steps:

Step 1: After obtaining informed consent, socio- demographic information was collected, followed by assessment of awareness regarding UCB banking using seven structured questions A minimum score of 0 and a maximum score of 1 were given to each, giving a cumulative score ranging from 0 to 7. Awareness was categorized as: No awareness: 0–2, Minimal awareness: 3–4, High awareness: 5–7.

Step 2: As part of the structured questionnaire, attitudes toward UCB banking were assessed. Before this section, participants were provided a brief educational input addressing common myths and facts to ensure informed and unbiased responses. This content was delivered verbally in the local language to ensure comprehension before proceeding to attitude assessment.

Attitude Assessment

Attitudes were measured using four structured, validated questions. Each favourable response was scored 1, and each unfavourable response 0. Total scores ranged from 0 to 4 and were categorized as: Positive attitude: 3–4 and Negative attitude: 0–2.

Dependent variables: Awareness level (categorical: No, minimal, high) and attitude (positive/negative). Independent variables: Age, parity, education, occupation, socioeconomic status, religion, and previous knowledge of UCB banking. All categorical variables were coded prior to analysis for consistency.

Data Management and Statistical Analysis

Data were entered and cleaned in Microsoft Excel and analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 20. Descriptive statistics (frequencies and percentages) were used for categorical variables. Associations between sociodemographic factors and awareness or attitude were tested using the Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Multivariable analysis was not performed as the study objective was mainly focused on descriptive and bivariate associations.

Ethical Considerations

The study was conducted after obtaining approval from the Research Ethics Committee of Gandhi Medical College, Secunderabad, (IEC/GMC/2025/02/02 -14) on March 07, 2025. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before data collection. Anonymity and confidentiality were maintained throughout the study. The study received no external funding.

RESULTS

In the present study, a total of 270 pregnant women were participated, majority of the sample (81.5%) is between the ages of 18 and 30. The Hindu population constitutes the largest religious group (45.2%). The vast majority of people (72.6%) come from nuclear families. The sample is predominantly from the lower middle socioeconomic class (44.4%). A significant proportion of the sample has completed high school (24.4%) or intermediate/diploma education (23.7%). The vast majority of people (80.0%) are unemployed or housewives. Multigravida (those with multiple pregnancies) account for 67.0% of the sample. 45.9% are in second trimester as per [Table. 1].

According to [Table. 2], among the study participants the most frequently cited source of information was the internet (5.1%), followed by healthcare professionals such as doctors (4.0%), family or friends (2.2%), and company representatives 0.3%. A significant proportion of participants (88.1%) reported having received no information regarding UCB banking. Knowledge of the types of UCB banks was found to be poor. Only 3.0% of participants were aware of public banks, 6.7% of private banks, and 2.2% were aware of both types. The remaining 88.1% were unaware of any type of UCB banking facilities.

Perceptions regarding the cost of UCB storage data were collected among 270 study participants. About 26.3% of respondents believed the cost to be less than ₹25,000, while 25.6% estimated it to be between ₹25,000 and

| Demographic Data | Frequency (Percentage) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 18-30 | 220(81.5%) |

| 31-40 | 50(18.5%) |

| Religion | |

| Hindu | 122(45.2%) |

| Muslim | 104(38.5%) |

| Christian | 40(14.8%) |

| Other | 4(1.5%) |

| Type of Family | |

| Nuclear | 196(72.6%) |

| Joint | 33(12.2%) |

| Extended nuclear | 41(15.2%) |

| Socio-economic Status | |

| Lower | 58(21.5%) |

| Lower middle | 120(44.4%) |

| Middle | 87(32.2%) |

| Upper middle | 5(1.9%) |

| Education | |

| Illiterate | 44(16.3%) |

| Primary | 22(8.1%) |

| Middle school | 30(11.1%) |

| High school | 66(24.4%) |

| Intermediate/diploma | 64(23.7%) |

| Under Graduate | 41(15.2%) |

| Post Graduate | 3(1.1%) |

| Occupation | |

| Employed | 54(20.0%) |

| Unemployed/housewife | 216(80.0%) |

| Parity | |

| Primigravida | 89(33.0%) |

| Multigravida | 181(67.0%) |

| Trimester of Pregnancy | |

| First | 51(18.9%) |

| Second | 124(45.9%) |

| Third | 95(35.2%) |

Table 1: Demographic data and frequencies of the study

population

₹50,000. A further 12.2% perceived the cost to be in the range of ₹50,001–₹75,000, and 14.1% believed it to fall between ₹75,001 and ₹1,00,000. Additionally, 15.9% estimated the cost to be between ₹1,00,001 and ₹5,00,000, while 8.1% believed it exceeded ₹5,00,000.

As per [Fig. 1], among the study participants majority of them 88.1% are unaware, 11.1% have minimal understanding of the UCB banking, while only a very few people 0.8% possess high awareness regarding UCB banking.

| Umbilical Cord Blood (UCB) Banking | Frequency (Percentages) |

|---|---|

| Source of Information | |

| Internet | 14(5.1%) |

| Doctor | 11(4.0%) |

| Family/Friends | 6(2.2%) |

| Representatives | 1(0.3%) |

| Lay Person | 0(0%) |

| None | 238(88.1%) |

| Type of Banks Exist | |

| Public | 8(3.0%) |

| Private | 18(6.7%) |

| Both | 6(2.2%) |

| Don’t Know | 238(88.1%) |

| What Do You Think the Cost of Storing UCB in Banks? |

|

| <25,000 | 71(26.3%) |

| 25,000 – 50,000 | 69(23.3%) |

| 50,001 – 75,000 | 33(12.2%) |

| 75,001 - 1,00,000 | 38(14.1%) |

| 1,00,001 – 5,00,000 | 43(15.9%) |

| >5,00,000 | 22(8.1%) |

Table 2: Awareness on Umbilical cord banking in the

study population

Fig. 1: Level of awareness towards Umbilical Cord Blood (UCB) Banking

As per [Fig. 2], among the study participants majority of them 64.8% of the individuals in the sample exhibit a negative attitude and 35.2% of then respondents display a positive attitude towards UCB banking.

As per [Table. 3], among the 270 pregnant women surveyed, A statistically significant association was observed between religion, socio-economic status, education, occupation, and parity with awareness levels (p < 0.05). Awareness was higher among Hindu participants compared to other religions (p = 0.002). Women belonging to the lower middle and middle socio-economic classes demonstrated greater awareness than those from lower or upper middle classes (p = 0.009). Education showed a strong positive correlation with awareness, which was highest among undergraduates and postgraduates (p < 0.001).

Similarly, employed women were more aware of UCB banking compared to unemployed or housewives (p < 0.001). Primigravida women also exhibited higher awareness levels than multigravida participants (p = 0.001). However, age, type of family, and trimester of pregnancy did not show any significant association with awareness levels (p > 0.05).

As per [Table. 4], a statistically significant associations were noted between age, religion, type of family, education, occupation, parity, and trimester of pregnancy with attitude (p < 0.05). Participants aged 18–30 years showed a more positive attitude compared to those aged 31–40 years (p = 0.001). Hindu participants exhibited a relatively more favorable attitude compared to other religious groups (p = 0.021).

Women from nuclear families had a significantly more positive attitude compared to those from joint or extended families (p < 0.001). Positive attitude increased with higher education levels (p < 0.001), and employed women had a more favorable attitude than unemployed or homemakers (p < 0.001). Primigravida women demonstrated a more positive attitude compared to multigravida women (p = 0.019). In addition, women in the first and second trimesters of pregnancy had a higher positive attitude than those in the third trimester (p = 0.002).

Fig. 2: Attitude towards Umbilical Cord Blood (UCB) Banking

| Predictor | Categories |

No awareness N=238 |

Minimal awareness N=30 |

High awareness N=2 |

Fisher’s exact (df) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | 18-30 | 190(86.4%) | 28(12.7%) | 2(0.9%) | 3.380, (2) | 0.154 |

| 31-40 | 48(96.0%) | 2(4.0%) | 0 | |||

| Religion | Hindu | 97(79.5%) | 23(18.9%) | 2(1.6%) |

19.192 (6) |

0.002 |

| Muslim | 101(97.1%) | 3(2.9%) | 0 | |||

| Christian | 36(90.0%) | 4(10.0%) | 0 | |||

| Other | 4(100.0%) | 0 | 0 | |||

| Type of family | Nuclear | 171(87.2%) | 23(11.7%) | 2(62.8%) | 1.396 (4) | 0.828 |

| Joint | 31(93.9%) | 2(6.1%) | 0 | |||

| Extended nuclear | 36(87.8%) | 3(12.2%) | 0 | |||

| Nuclear | 171(87.2%) | 23(11.7%) | 2(62.8%) | |||

| Socio economic status | Lower | 56(96.6%) | 2(3.4%) | 0 | 15.302 (6) | 0.009 |

| Lower middle | 97(80.8%) | 22(18.3%) | 1(0.8%) | |||

| Middle | 81(93.1%) | 5(5.7%) | 1(1.1%) | |||

| Upper middle | 4(80.0%) | 1(20.0%) | 0 | |||

| Education | Illiterate | 44(100.0%) | 0 | 0 | 79.731 (12) | <0.001 |

| Primary | 21(95.5%) | 1(4.5%) | 0 | |||

| Middle school | 29(96.7%) | 1(3.3%) | 0 | |||

| High school | 63(95.5%) | 3(4.5%) | 0%) | |||

| Intermediate/diploma | 62(96.9%) | 1(1.6%) | 1(1.5%) | |||

| UG | 19(46.3%) | 21(51.2%) | 1(2.5%) | |||

| PG | 0(0%) | 3(100.0%) | 0(%) | |||

| Occupation | Employed | 34(63.0%) | 19(35.2%) | 1(1.9%) | 33.613 (2) | <0.001 |

| Unemployed/house wife | 204(94.4%) | 11(5.1%) | 1(0.5%) | |||

| Parity | Primigravida | 70(78.7%) | 17(19.1%) | 2(2.2%) | 11.940 (2) | 0.001 |

| Multigravida | 168(92.8%) | 13(7.2%) | 0 | |||

| Trimester of pregnancy | First | 44(86.3%) | 7(13.7%) | 0 |

4.256 (4) |

0.317 |

| Second | 106(85.5%) | 17(13.7%) | 1 | |||

| Third | 88(92.6%) | 6(6.3%) | 1(1.1%) |

Table 3: Predictors of Awareness of UCB banking

Abbreviations: df = degrees of freedom

DISCUSSION

The present study aimed to assess awareness, attitudes, and practices regarding umbilical cord blood (UCB) banking among 270 pregnant women. It highlights critical knowledge and perception gaps, underscoring the need for improved antenatal education and public health communication.

Awareness of UCB Banking

Only 11.1% of participants demonstrated minimal awareness, and 0.8% had high awareness, while 88.1% had none. These findings align with Indian studies such as Anandgaonkar et al [8] in Telangana, where 27% of couples had heard of UCB banking but lacked detailed knowledge about public versus private systems. Similarly, K P et al. [12] and R C et al. [11] found poor awareness among semi-urban and Puducherry populations, respectively. Mistry et al. [9] even reported gaps among obstetricians, especially regarding public banking and its indications.

Most women in the current study were young (18–30 years), unemployed, and from lower-middle socioeconomic backgrounds. Pandey et al. [6] similarly noted that even educated women often lacked UCB knowledge, indicating that formal education does not necessarily translate into health literacy. Tuteja et al. [2] and Mistry et al. [9] also reported poor awareness among unemployed and lower socioeconomic groups, while Anandgaonkar et al. [7] observed that multigravida status did not improve awareness. In contrast, Fernandez et al. [3] and Jordens et al. [13] reported higher awareness in high-income, educated women in Canada and Australia, highlighting disparities between developed and developing settings.

Information sources were mostly informal—internet (5.1%), doctors (4%), family/friends (2.2%), and company representatives (0.3%). This pattern resembles findings by Tuteja et al. [2] and Pandey et al. [6], where private marketing outweighed medical counseling. Only 3.0% and 6.7% knew about public and private UCB banks, respectively, consistent with studies by Yadav et al. [14] and Viswanathan et al. [5], who emphasized that public donation remains poorly promoted.

| Predictor | Categories |

Negative attitude N=175 |

Positive attitude N=95 |

Χ² (df) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 18-30 | 132(60.0%) | 88(40.0%) | 12.077 (1) | 0.001 |

| 31-40 | 43(86.0%) | 7(14%) | |||

| Religion | Hindu | 69(56.6%) | 53(43.4%) | 10.156* (3) | 0.021* |

| Muslim | 79(76.0%) | 25(24.0%) | |||

| Christian | 24(60.0%) | 16(40.0%) | |||

| Other | 3(75.0%) | 1(25.0%) | |||

| Type of family | Nuclear | 123(62.8%) | 73(37.2%) |

19.58 (2) |

<0.001 |

| Joint | 26(78.8%) | 7(21.2%) | |||

| Extended nuclear | 3(63.4%) | 15(36.6%) | |||

| Socio economic status | Lower | 34(58.6%) | 24(41.4%) | 7.816 (2) | 0.05 |

| Lower middle | 71(59.2%) | 49(40.8%) | |||

| Middle | 66(75.9%) | 21(24.1%) | |||

| Upper middle | 4(80.0%) | 1(20.0%) | |||

| Education | Illiterate | 36(81.8%) | 8(18.2%) | 42.979 (6) | <0.001 |

| Primary | 16(72.7%) | 6(27.3%) | |||

| Middle school | 24(80.0%) | 6(20.0%) | |||

| High school | 41(62.1%) | 25(37.9%) | |||

| Intermediate/diploma | 47(73.4%) | 17(26.6%) | |||

| UG | 11(26.8%) | 30(73.2%) | |||

| PG | 0 | 3(%) | |||

| Occupation | Employed | 20(37.0%) | 34(63.0%) | 22.838 (1) | <0.001 |

| Unemployed/housewife | 155(71.8%) | 61(28.2%) | |||

| Parity | Primigravida | 49(55.1%) | 40(44.9%) | 5.544 (1) | 0.019 |

| Multigravida | 126(69.6%) | 55(30.4%) | |||

| Trimester of pregnancy | First | 26(51.0%) | 25(49.0%) | 12.427 (2) | 0.002 |

| Second | 75(60.5%) | 49(39.5%) | |||

| Third | 74(77.9%) | 21(22.1%) |

Table 4: Predictors of Attitude of UCB banking

Abbreviations: χ² = chi-square; df = degrees of freedom; * = Fischer’s Exact test.

Hodges et al. [10] in Chennai also noted that emotional, commercial marketing dominates, creating confusion and mistrust.

Reasons for Low Awareness

Low awareness in India largely stems from the absence of structured antenatal counseling, inadequate provider knowledge, and limited promotion of public banking. R C et al. [11] and Mistry et al. [9] found that discussions on UCB banking rarely occur in government hospitals. Tuteja et al. [2] highlighted that even healthcare professionals lack training. Public banks are scarce and poorly advertised, giving the impression that UCB banking is an expensive private service. Hodge et al. [10] further observed that emotional advertising replaces evidence-based information. Low health literacy and economic constraints compound these barriers, especially in rural or low-income settings.

Attitudes Toward UCB Banking

In this study, 64.8% of women showed a negative attitude, while 35.2% had a positive one—findings consistent with Anandgaonkar et al. [7], Pandey et al. [6], Pisula et al. [15], and Jordens et al. [13]. This indicates a gap between limited awareness and positive perceptions, influenced by misinformation, cost concerns, and poor counselling.

Understanding of UCB Types and Costs

About 87.8% were unaware of differences between public and private banks-an important determinant of attitude. Waller-Wise [16] reported similar confusion even in developed countries. Cost perceptions varied widely: 26.3% estimated below ₹25,000, 25.6% between ₹25,000–₹50,000, and others up to ₹5,00,000. Such inconsistency reflects poor information, as also seen in Saleh et al. [17] and Armson et al. [4], where high-cost perceptions deterred participation. Hodges et al. [10] and Mistry et al. [9] observed that in India, UCB banking is viewed as a luxury for affluent families due to lack of awareness about free public donation.

Socio-Demographic Influences on Attitude

Significant associations were found between attitude and age, education, occupation, parity, religion, and pregnancy trimester. Younger and more educated women had more favorable attitudes, consistent with Fernandez et al. [3], Jordens et al. [13], and Pandey et al. [6]. Education and employment improved awareness, as also reported by R C et al. [11] and Anandgaonkar et al. [7]. Women from higher socioeconomic strata were more receptive, reflecting findings from Saleh [17], Lu et al. [18], and Viswanathan et al. [5]. In contrast, most participants in the present study belonged to lower-middle-class nuclear families, potentially limiting access to reliable information.

Structural and Accessibility Barriers

Despite some interest, none of the participants practiced UCB banking, echoing studies by Anandgaonkar et al. [7] and Viswanathan et al. [5], who reported underutilization of public facilities due to lack of infrastructure and awareness. The unavailability of collection services in public hospitals and the absence of government promotion make UCB banking inaccessible for most women. Hodges et al. [11] similarly described skepticism arising from private sector dominance and inadequate public initiatives.

Role of Healthcare Providers

Only 4% of participants received information from doctors, reflecting minimal involvement of healthcare professionals. Tuteja et al. [2] and Mistry et al. [9] noted that many clinicians lack formal knowledge or defer counselling to private representatives, leading to biased information. This limited engagement fosters mistrust and negative attitudes. In contrast, countries where UCB banking is included in routine antenatal counselling—such as the U.S. and Canada—report higher acceptance (Waller-Wise [16]). Integrating UCB education into antenatal care in India could therefore improve informed decision-making.

Practice of UCB Banking

No participants had banked cord blood, reflecting a complete absence of practice despite moderate interest. Similar findings were observed in Anandgaonkar et al. [7], R C et al. [11], and Mistry et al. [9]. Key barriers include lack of awareness about public banking, perceived high cost of private banking, and lack of counselling during pregnancy. Viswanathan et al. [5] reported that India’s first public bank remained underutilized due to poor outreach, while Hodges et al. [10] attributed low uptake to confusion and mistrust created by aggressive private marketing.

CONCLUSION

The study reveals alarmingly low awareness and poor attitudes toward UCB banking among pregnant women, despite its potential public health benefits. Education level, occupation, and socioeconomic status significantly influenced knowledge and perception. Limited counselling by healthcare providers, poor promotion of public banking, and misconceptions regarding cost and purpose remain major deterrents. Strengthening antenatal counselling, training healthcare providers, and expanding public banking awareness through government and media initiatives are essential to bridge the gap between awareness and practice and ensure equitable access to this valuable resource.

LIMITATIONS

A limitation of this study is its focus on a single tertiary care hospital, which may not fully represent the broader population of pregnant women in Hyderabad or India. Further research involving larger, multi-centre samples and including more rural areas could provide a more comprehensive understanding of awareness and practices across different populations. The study was also restricted by its sampling window, as data collection occurred only between 10:00 AM and 12:00 noon in the OPD, potentially excluding women who attend at other times; this may have introduced selection bias, since healthcare-seeking patterns, occupation, or socio-economic status could differ among women visiting outside this timeframe. By focusing exclusively on pregnant women, the study may have overlooked critical perspectives and interpersonal dynamics that influence actual practice and uptake of UCB banking. Additionally, the study did not include family members such as husbands, parents, or guardians, limiting the understanding of collective decision-making contexts common in many Indian households. Other methodological limitations include the reliance on self-reported responses, which are prone to recall and social-desirability bias, the absence of multivariable analysis limiting identification of independent predictors, and the lack of reliability or validity testing of the attitude scale beyond Cronbach’s α.

RECOMMENDATIONS

To address the gaps identified in the study, targeted educational campaigns are essential. Information about UCB banking should be made more accessible and understandable, especially for women from lower socio-economic backgrounds. Healthcare professionals, particularly obstetricians and pediatricians, must be actively engaged in counselling pregnant women about the potential benefits and availability of UCB banking. Policies should consider making it more affordable or accessible for women from lower socioeconomic backgrounds. Financial support, subsidies, or government-backed programs could help alleviate concerns about cost. Furthermore, the use of digital platforms and social media could be leveraged to reach a larger audience, especially in rural areas where traditional media may not be as effective.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

1. Umbilical Cord Blood Banking. [cited 2024, Dec 16]. Available from: https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/ committee-opinion/articles/2019/03/umbilical-cord-blood-banking

2. Tuteja M, Agarwal M, Phadke SR. Knowledge of Cord Blood Banking in General Population and Doctors: A Questionnaire Based Survey. The Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 2016; 83 (3). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12098-015-1909-x

3. Fernandez CV, Gordon K, Van den Hof M, Taweel S, Baylis F. Knowledge and attitudes of pregnant women with regard to collection, testing and banking of cord blood stem cells. CMAJ. 2003 Mar 18;168(6):695–8.

4. Armson BA, Allan DS, Casper RF. Umbilical Cord Blood: Counselling, Collection, and Banking. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada. 2015; 37 (9). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/s1701-2163(15)30157-2

5. Viswanathan C, Kabra P, Nazareth V, Kulkarni M, Roy A. India’s first public cord blood repository — looking back and moving forward. Indian Journal of Hematology and Blood Transfusion. 2009; 25 (3). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12288-009-0023-5

6. Pandey D, Kaur S, Kamath A. Banking Umbilical Cord Blood (UCB) Stem Cells: Awareness, Attitude and Expectations of Potential Donors from One of the Largest Potential Repository (India). PLOS ONE. 2016; 11 (5). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0155782

7. Anandgaonkar RK, Motwani R, Ramaswamy G, Patnaik N. Awareness and Attitude of Pregnant Couple Toward Umbilical Cord Blood Banking in Telangana: A Cross-sectional Study. Indian Journal of Community Medicine. 2024; 49 (4). Available from: https://doi.org/10.4103/ijcm.ijcm_779_23

8. Ballen KK, Gluckman E, Broxmeyer HE. Umbilical cord blood transplantation: the first 25 years and beyond. Blood. 2013; 122 (4). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2013-02-453175

9. Mistry AA, Amin AA, Nimbalkar SM, Bhadesia P, Patel DR, Phatak AG. Knowledge of umbilical cord blood banking among obstetricians and mothers in Anand and Kheda District, India. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care. 2018; 7 (5). Available from: https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_147_18

10. Hodges S. Umbilical cord blood banking and its interruptions: notes from Chennai, India. Economy and Society. 2013; 42 (4). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/03085147.2013.772759

11. Catherine R, Akishya M, Raji D, Revathi P, Saranya K, Shahana I, et al. Knowledge and attitude regarding umbilical cord blood banking among antenatal mothers in OPD at Pondicherry Institute of Medical Sciences, Puducherry. The New Indian Journal of OBGYN. 2020; 6 (2). Available from: https://doi.org/10.21276/obgyn.2020.6.2.7

12. Poomalar GK, Jayasree M. Awareness of cord blood banking among pregnant women in semi urban area. International Journal of Reproduction, Contraception, Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2016; Available from: https://doi.org/10.18203/2320-1770.ijrcog20162629

13. Jordens CFC, Kerridge IH, Stewart CL, O’Brien TA, Samuel G, Porter M, et al. Knowledge, Beliefs, and Decisions of Pregnant Australian Women Concerning Donation and Storage of Umbilical Cord Blood: A Population‐Based Survey. Birth. 2014; 41 (4). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/birt.12121

14. Yadav N, D’Souza VL, Geethamani T. Assessment of Knowledge and Attitude Among College Students Toward Umbilical Cord Blood and its Banking. Nepal Journal of Health Sciences. 2021; 1 (1). Available from: https://doi.org/10.3126/njhs.v1i1.38493

15. Pisula A, Sienicka A, Stachyra K, Kacperczyk-Bartnik J, Bartnik P, Dobrowolska-Redo A, et al. Women’s attitude towards umbilical cord blood banking in Poland. Cell and Tissue Banking. 2021; 22 (4). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10561-021-09914-y

16. Waller-Wise R. Umbilical Cord Blood Banking. The Journal of Perinatal Education. 2022; 31 (4). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1891/jpe-2021-0006

17. Saleh FA. Knowledge and Attitude Among Lebanese Pregnant Women Toward Cord Blood Stem Cell Storage and Donation. Medicina. 2019; 55 (6). Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina55060244

18. Lu H, Chen Y, Lan Q, Liao H, Wu J, Xiao H, et al. Factors That Influence a Mother’s Willingness to Preserve Umbilical Cord Blood: A Survey of 5120 Chinese Mothers. PLOS ONE. 2015; 10 (12). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0144001

Copyright

©2025 (Lavudi et al). This is an open-access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License CC-BY 4.0. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original authors and source are credited.

Cite this article

Lavudi SC, Sushmitha T, Kumar GV, Koteshwaramma C, Chand TR. Awareness, Attitude and Practice Towards Umbilical Cord Blood Banking among Pregnant Women in Tertiary Care Hospital, Hyderabad. Perspectives in Medical Research 2025; 13(3):183-190 DOI: 10.47799/pimr.1303.25.21